by Paul Hislip, Communications intern (Class of 2018)

In July 2016, the City Council of Newark, NJ added a new chapter to its zoning and land use regulations. “Environmental Justice and Cumulative Impacts” is intended to create stronger environmental and land use policy tools at the local level to prevent and mitigate additional pollution associated with a variety of development and redevelopment projects. It also addresses environmental justice by helping to prevent Newark, which has a disproportionate number of low-income and residents of color, from having a disproportionate number of polluting projects placed within its borders.

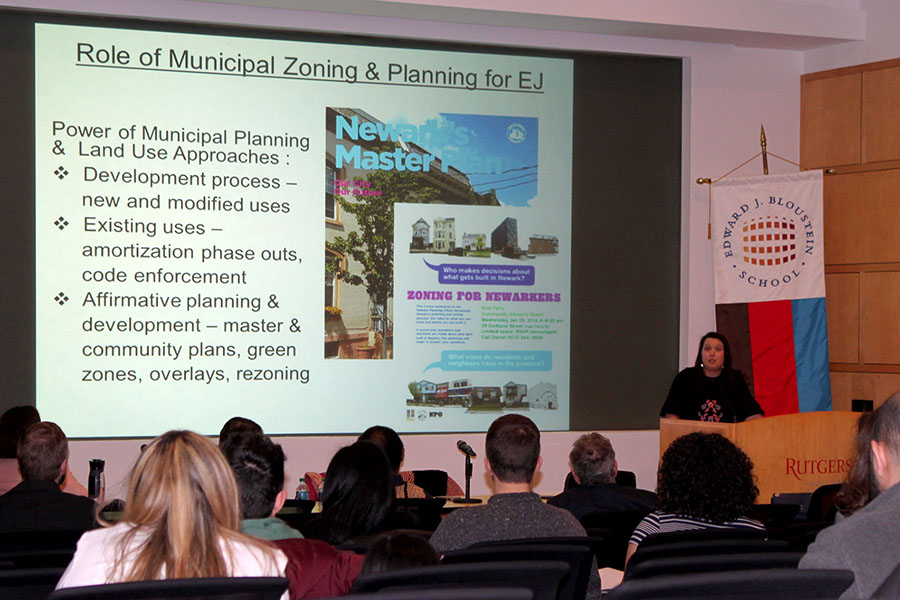

This was the topic of the Bloustein School’s spring 2017 Robert A. Catlin Memorial Lecture. Three panelists discussed the various components and impacts of the ordinance.

Dr. Nicky Sheats, Esq., Director of the Center for the Urban Environment at the John S. Watson Institute for Public Policy, Thomas Edison State University, opened the Catlin lecture with a discussion of the backdrop for the conditions that prompted development of the ordinance and the rationale among advocates and local officials for pursuing an approach focusing on land use. Some of the questions he focused on were, how do multiple pollutants interact with each other in an environment, and what social implications do they have? What do these pollutants mean for the community? And finally, while governments attempt to regulate pollutants in a way that does not breach individuals’ standards, how are those standards defined?

Dr. Sheats provided a real-world example of a cumulative impact—suppose the city council wants to build a new power plant in Newark’s Ironbound district, an area that already struggles with pollution. The city’s response would probably be along the lines of “well, this isn’t violating any individual’s standards so there isn’t much we can do.”

The government’s standards may not align with individual standards and unfortunately, individual standards are not yet been translatable to laws. Dr. Sheats pointed out that “There are no divisions in our lungs” that determine how humans experience pollutants. He showed a graph developed by environmental justice community organizers, which detailed the differences between communities that experience pollution versus the predominant race of those communities, which showed that as the number of people of color or the level of poverty in a neighborhood increased, so too did the cumulative impacts. In New Jersey, the amount of pollution you experience is directly correlated to your income and skin color.

Dr. Sheats also discussed a comprehensive timeline explaining the history of environmental justice in New Jersey since 2001. He concluded with an explanation of the “guts” of the original EJ ordinance in Newark. This ordinance required lists of pollutants that exist in the environment to be overlaid on demographic information, as well as for information on new potential pollutants from commercial or industrial complexes. A portion that—much to Dr. Sheats’ chagrin—did not make it into the ordinance was a clause that gave residents the right to say no to new pollutants through a direct referendum.

Dr. Ana Baptista EJB Ph.D. ’08, an Assistant Professor of Professional Practice in Environmental Policy and Sustainability Management and Associate Director at the Tishman Environment & Design Center at The New School, and a former student of Dr. Catlin, moved the conversation along to the topic of race in policy. Paying homage to Dr. Catlin, she argued that land use policy contains very deep institutionalized racism; industries like home lending and banking have historically been in favor of the upper class and noting, “Places like Newark can’t exist without places like Short Hills.”

She explained that zoning laws in Newark are slowly changing, including rezoning and getting rid of outdated rules that were grandfathered in. But the impacts from the pollutants that were allowed to run rampant are very evident. Before Newark’s zoning laws were updated in 2012, the last time they had been updated was in 1954 and therefore had little regard for quality-of-life issues. The Ironbound district later became a hotbed for environmental justice movements due to its adjacency to industrial areas. Many heavy pollutants that were planned for this area saw heavy protest from EJ activists, like automobile shredding plants and chicken crematoriums. Sometimes, these projects were planned just feet away from low-income housing. Dr. Baptista focused heavily on the importance of fair zoning boards and of advocating for change.

Finally, she discussed the ordinance itself. Applying Kingdon’s model, which notes that agenda setting is the first stage in the policy process to the Newark environmental justice ordinance, Dr. Baptista highlighted Kingdon’s political stream; in other words, the timing and the mood to push policy through a given window of opportunity, which usually changes after major elections. The election of Newark mayor Ras Baraka allowed the EJ community to get their ordinance passed. The ordinance itself requires individuals applying for commercial or industrial developments within Newark to take the following steps:

- Reference the city’s ERI and prepare a checklist of pollutants

- Submit checklist and development application to the city

- Checklist goes to the Environmental Commission

- Checklist goes to the Planning or Zoning Board (where appropriate)

The public has full access to this checklist to weigh in on it and make their voices heard.

Cynthia Mellon, co-chair of the City of Newark Environmental Commission and Coordinator of the Newark Environmental Resource Inventory, concluded the lecture by discussing what it is like to get an ordinance implemented. She began by explaining that Newark’s environmental justice ordinance is a landmark policy, as it is the first of its kind in a major New Jersey city, and other cities and communities have thus expressed great interest in it. Newark’s policy was advanced through advocacy and community organization. Ms. Mellon provided a snapshot of Newark’s environmental checklist, and in particular the top five problems Newark faces: truck trips giving off diesel emissions, particulate from other sources (for example, grain storage), emissions from vehicle idling, low tree cover, and impervious surfaces. Her lecture concluded with a listing of some very valuable resources for aspiring environmental justice activists.

The Robert A. Catlin Memorial Lecture honors the legacy of Robert A. Catlin, Bloustein School professor, who died in July 2004. Catlin began his career as a staff planner for governmental agencies and community organizations in several cities, including Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and New York. He also served as dean of the College of Social Science at Florida Atlantic University, dean of the Camden College of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers, and provost and vice president for academic affairs at California State University, Bakersfield. He was inducted as an AICP Fellow in 2001. At the Bloustein School, he specialized in urban revitalization, planning, and the impact of race in public policy decision-making, which are the themes of the annual lecture.