Lisa K. Bates, Ph.D., Associate Professor at Portland State University in the Toulan School of Urban Studies and Planning and Portland Professor in Innovative Housing Policy recently presented the Bloustein School’s Stuart Meck Distinguished Lecture in Land Use and Affordable Housing. In the lecture, titled “’We shall seek social justice’: From aspiration to implementation of Portland’s urban planning,”

Also affiliated with PSU’s Black Studies department, Dr. Bates’ scholarship focuses on housing and community development policy and planning, and her research and practice aim to build new models for emancipatory planning practices and to dismantle institutional racism.

In the lecture, Dr. Bates stated that her goal is to move social justice from aspiration to reality. This can be achieved by communities taking the lead in redevelopment and renewal rather than plans being implemented by city agencies and planners.

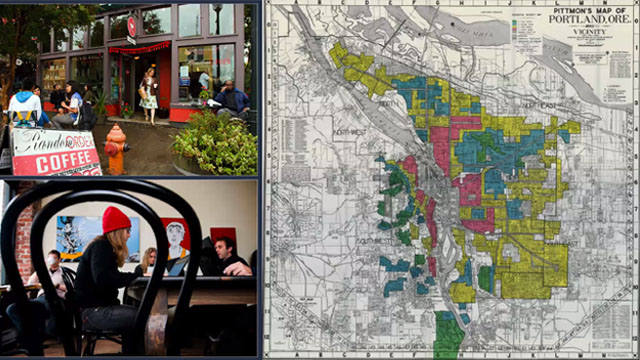

Dr. Bates gave a brief history of planning and community development in Portland, Oregon, noting that Portland, like many cities, had been white and the demographics changed during World War II as blacks came from the south to work in the Kaiser shipyards. This change alarmed white Oregonians. At the time, Oregon was a “sun-down state,” meaning Blacks could not be out after sundown. In addition, Blacks could not stay in the state for more than four days, and Ku Klux Klan activity was high. When Blacks moved into Portland, they were steered into the Albina district, a red-lined community targeted for “urban renewal.”

Members of the Albina community pushed back, questioning the planning model of blighted neighborhoods. They pointed out that poor, white communities received funding to repair dilapidated housing and blocks while struggling Black communities were torn down. The Albina community said that a ghetto had been created by red-lining and in turn, the city felt the need to tear down that community. Eminent domain was used to demolish Black business districts and create parking lots for hospitals and clinics. This created a cascading effect of disinvestment in the Albina community. Red-lining had created a blueprint for slum creation.

Contract purchasing was one of the tactics used to ensure that Blacks overpaid for housing and paid higher than market-level interest rates, thereby never having the opportunity to own their homes. They became heavily in debt and could no longer borrow money at competitive interest rates. In addition, they could not pass on intergenerational wealth as no wealth had been created and the capacity to create intergenerational wealth had been destroyed due to a lack of access to credit.

In 1993, the Albina Community Plan was developed. It examined how to create community, safety, job training, and child care to preserve the community and addressed decades of need. Its foundation was the creation of the basic infrastructure needed for the community to thrive.

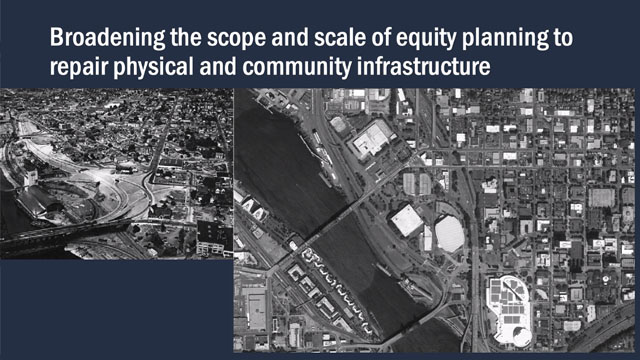

The year 2000 saw the creation of an Urban Renewal Area. The Hope 6 Projects were mixed-income housing and tied to a light rail system. Light rail often leads to gentrification and significant disruption of housing. The community saw the gentrification of their neighborhood as inevitable. The Interstate Alliance to End Displacement was formed to end displacement caused by the location of interstate highways. This had typically been done by locating interstate highways through economically depressed neighborhoods. The community insisted that planners make sure that Albina residents were not displaced as they were when the sports stadium and connecting highways were built in the 1970s and 1980s.

Dr. Bates noted that again, this didn’t happen. In 2010 no neighborhood in Portland was predominantly Black. Albina residents were moved to East Portland, an “outer neighborhood” with unimproved, gravel roads, no pedestrian walkways, no places to buy food, and far away from the central features of African American civic activities such as schools, churches, public health clinics, and parks.

The community asked several questions of planners, developers, and the city government: why worry about bike lanes when the community didn’t have bus service? How does equity planning become real? How do we repair and restore communities after the destruction of communities brought about by urban renewal?

Northeast Portland needed to be stabilized, and a right to return and a right to stay needed to be established. Families and their descendants who were displaced by urban renewal needed to be able to return to the community. The community didn’t need gentrification; it needed the return of the community that was dispersed. This would provide economic activity to stabilize and revitalize the business community that had already existed. The city had records of who lived in the community and used these records along with other documentation to reach out to property owners and their descendants.

Dr. Bates explained that while the right of return is not limited to the former Black residents of the community, they are the ones taking the greatest advantage of it.

This has led to community members pushing for a discussion and implementation of urban redevelopment of Portland. The community emphasized the need for equity in housing, transportation, and civic services throughout communities of color in Portland. Community Preservation is now defined as socio-economic diversity and cultural stability. Community members engaged communities of indigenous societies and other communities of color to make proposed changes and renovations to the I-5 corridor beneficial to the communities that had been there.

Dr. Bates also highlighted the work of the African American Leadership Forum and their “Imagine Black” initiative. Imagine Black asks the question: What would our cities look like if we loved the Black community? How would our cities look if Blacks were pacemakers? How can we make our vision of social justice real, and how can move forward together?