by Michael L. Lahr, Rutgers Economic Advisory Service for New Jersey State Policy Lab

Here we are in mid-March of 2022 and the average price of a gallon of regular-grade gasoline in New Jersey is $4.335; a year ago it was $2.925.[1] That’s nearly a 50% increase in less than a year. How and why did it come to this? Are oil companies or local gas station franchises gouging us? Is the Russian invasion of Ukraine causing this? What’s going on?

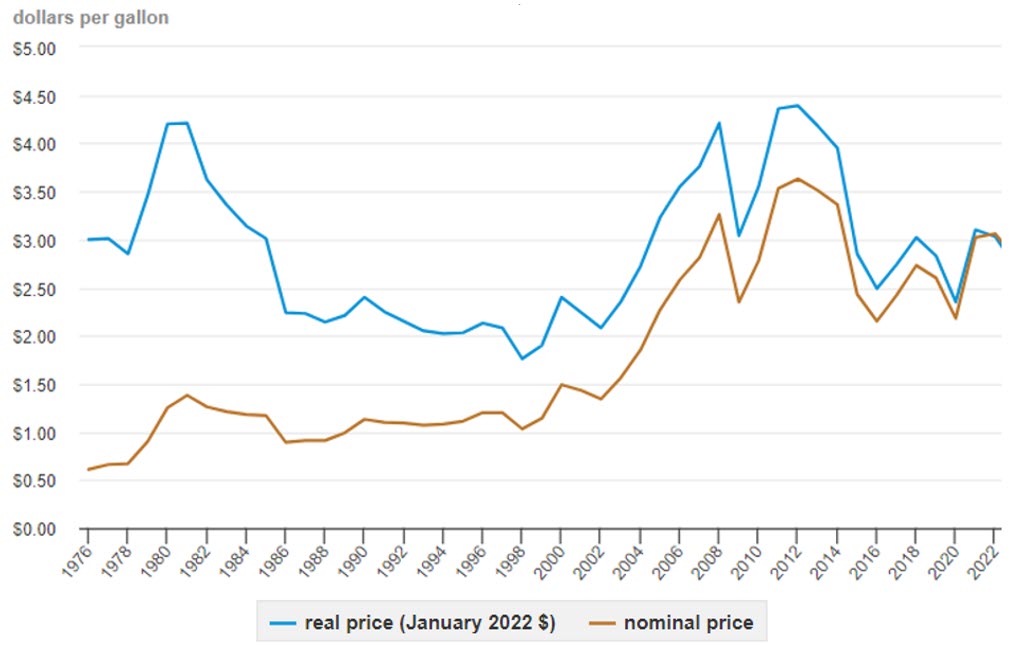

The answer to these and a myriad of other related questions is quite complicated. Let me start by saying that some of this rise should have been expected. In late April to early May 2020, real gasoline prices were close to the low prices we got accustomed to here in the U.S.A from 1986 to 2004 but have not experienced since (see Figure 1). By “real,” I mean if we convert all historical gasoline prices by inflating them into a dollar to which we can sort of relate. In this case, one that existed as recently as January 2022. And, while gasoline prices from a year ago (about $3.00 per gallon) were something close to the 2004-2021 average, they tend to vacillate regularly and widely, as most commuters are painfully aware.

Figure 1: U.S. Average annual regular-grade gasoline prices, January 1976- January 2022

Source U.S. Energy Administration. Short Term Outlook, January 2022.

Available online in March 2022 at https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/gasoline/prices-and-outlook.php

Note: Retail prices including taxes.

Still, there are at least four key factors that can drive up prices. Only two of them (the first two) are not affecting matters at all presently:

- Motor fuels and/or petroleum products gross receipts taxes can play a role, but only when they rise.

In 2016, a new tax was added to the price of gasoline in New Jersey, increasing taxes on a gallon of gasoline from 14.5 to 50.7 cents/gallon.[2] It has since declined by 8.3 cents/gallon.[3] Still, there are presently calls across many states for reductions in state or federal taxes.[4] - The relative value of the U.S. dollar vis-à-vis other world currencies, particularly the Euro, plays a role. Most oil contracts are established in U.S. dollars. So, if the value of the dollar declines relative to that of other currencies, it costs less for Americans to buy crude oil.

The U.S. economy and dollar are strong compared to other world economies and currencies. The relative value of the dollar is presently a non-issue. - Lower-than-usual supply occurs when factors like wars or natural disasters cause oil-producing countries to reduce their output. It also happens when OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) members reduce their production quotas.

OPEC member nations, particularly Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates, have not been producing as much crude oil as promised over the past year.[5] Furthermore, Russia’s aggressions against Ukraine are playing a role via sanctions on trade with Russia, the second-largest oil-exporter in the world. The U.S. and trade partners in Europe are also not so friendly with Iran, another nation that could help out with oil supplies. This all is generating shortages. It does not help that demand is coincidentally rising as the world rebounds from the pandemic. - Higher-than-usual demand can similarly affect oil and gasoline prices. For example, we experience such demand-based gasoline price rises each summer as we embark on our vacations.

Global oil demand is not anticipated to rise in an extraordinary manner. Still, it is certainly not anticipated to falter either. This coupled with a substantial reduction in supply due to sanctions against Russia suggest that spot price of Brent oil[6] (a blend of oil from the North Sea) could rise another 50% over the next year.[7] - Refiners increase their margins when markets for petroleum products are tight. It does not help American consumers when the U.S. refineries shutter permanently.[8]

This has been the case for the last half year at least in the U.S.[9] But the refiners’ margin is only about 12%, so the experienced rises are not in the “worry zone.”[10] - Transportation margins rise with crude oil prices.

While this is certainly part of the story, like refiners’ margins, it is a similar small part of the action. The only thing less likely is a rise in retailers’ margins. Gas stations are very competitive, so if one of them appears to gouge, customers notice immediately and retaliate by purchasing down the road. - Commodity exchanges (markets akin to Wall Street) also play a major role in gasoline prices since both oil and gasoline are commodities. Commodities exchanges establish futures contracts, which are agreements to buy or sell a raw material at a specific date in the future at a particular “spot” price. Buyers are trying to hedge against prices rising too high; Sellers use futures to guarantee the price they will receive. In this vein, spot prices of oil and gas futures vacillate like stock prices, because they depend on what investors anticipate the price of oil or gasoline is likely to be at some point in the future. In fact, commodities traders combine to be a major factor in determining day-to-day fluctuations in oil prices since gasoline station operators follow spot prices, not longer-term contract prices — even though most petroleum products are traded via prices established in long-term contracts, not spot prices.

The key here is that commodities futures can reflect the sentiment (emotion or belief) of the trader or the market rather than supply and demand. Speculators bid up prices to make a profit if a crisis occurs and they anticipate a shortage. That is, buyers and sellers essentially bet on what they believe the future prices of these commodities might be. Much of the run up in gasoline prices over the last couple of weeks has been caused by changes in spot prices of oil. It seems odd and perhaps unfair, even though sanctions were not yet in place, that oil prices rose (and, hence, also gasoline prices). The oil for which the price was rising was, after all, at best in a tanker or a storage tank somewhere. It could not actually be the price of gasoline pouring into your tank.

Ultimately, although Brent oil prices appear to be wavering, higher prices at the pumps are likely to remain. Commodities buyers and sellers are simply not yet perceiving clear outcomes for the conflict in the Ukraine or for the impacts of global economic sanctions on Russia.

Higher prices are on the horizon due to the way gasoline stations buy the fuel and the time lag between when they purchase gasoline at a high price and when they have totally sold that particular allotment of gasoline. Further, some retailers might be reluctant to lower prices for fear that wholesale costs of gasoline will rise again.

References