Historic urban planning and policy decisions have led to higher impacts of COVID-19 in low-income communities. As future planners and policymakers, it is our responsibility to consider how we can un-do these dynamics while working hand-in-hand with low-income communities to fight forward processes of self-determination and economic democracy.

In September, the Bloustein Graduate Student Association held a virtual interactive seminar with community organizers and planners from MIT Community Lab Innovators (CoLab). Nick Shatan MCRP ’17, Learning Manager for CoLab and Lawrence Haseley, Project Manager, Participatory Planning for CoLab, engaged in a conversation regarding creating just economies and self-determination in the aftermath of the COVID pandemic.

They focused on the Bronx Development Cooperative Initiative as an example of the type of organization that is looking to create a more just and sustainable economy in the Bronx. The Initiative has assisted with the creation of three components through community leadership. The first, the Bronx Innovation Factory, sought to bring advanced manufacturing to the Bronx despite the challenges of locating manufacturing space in the Bronx. This led to the use of 3-D printers to manufacture PPE masks. The Bronx Exchange created a procurement system wherein businesses, community organizations, health care providers, and schools could procure supplies from local business, and thereby, keep dollars in the local community. The Planning and Policy Lab was developed to assist community efforts to decommodify land in order to stop gentrification.

Haseley detailed the tactics used to prevent the closure of safety-net Interfaith Hospital in Brooklyn. While the community was successful in keeping the hospital open, he said, they felt obligated to address the health care disparities that existed in the neighborhood. The Brooklyn Communities Collaborative gave voice to the local community and advanced the idea of community inquiry to investigate community needs rather than reliance on external organizations to set the community’s agenda. They in-turn founded the East Brooklyn Call to Action which included students and organized labor to examine the social determinants of health and health care disparities.

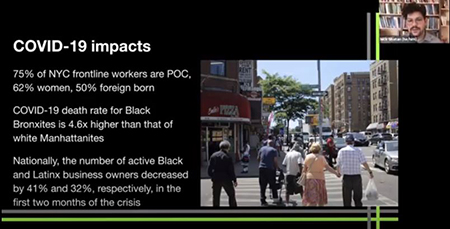

The East Brooklyn Call to Action found that 75% of frontline health care workers are people of color; 62% of frontline health care workers are women; 50% of frontline health care workers are foreign-born; the COVID death rate for Black Bronxites is 4.6 times higher than for white Manhattanites; Black-owned businesses have declined by 41% nationally, and Latinx owned businesses have declined by 32% nationally.

What would a just recovery look like?

Haseley said that the future of planning has to evolve in order to stay relevant. It needs make fundamental changes in terms of how it trains practitioners and engages with other professions. It would need to be decentralized and participatory. Often, plans are designed without including those for whom the plan is for; everyone needs to be part of the conversation. Democratic control and ownership would also be fundamental, which leads to the intersectionality of things by using the lenses of race, gender, ability, sexuality, and indigenous people’s rights when thinking through different projects and plans. “As planners, we need to look at what planning needs to look like for it to have meaningful impact, especially now in 2020. I think that’s something we all have to ask ourselves,” he concluded.

Shatan provided some examples as to what it could look like, noting that a post-COVID recovery should expand democratic ownership of land and housing. “This way, communities band together and make decisions together through their shared ownership, rather than piecemeal speculation that would affect the neighborhood. This is important for environmental resilience, which will be important for COVID recovery,” he said. Incorporating sustainable, health-related manufacturing space as part of mixed-use projects will generate local jobs, and providing funding to support community wi-fi and solar power networks will increase resilience and just energy transition.

In conclusion, they stressed the importance of thinking about post-COVID recovery through the lenses of environmental justice, restorative justice, healing, and more. It would include investing in community care and healing, including redistributing funds toward community-based models that would work towards violence and harm reduction and crisis intervention, reframing community land trusts to fight for environmental justice and resilience, and developing Municipal Procurement Trusts.