Thomas Craemer, Ph.D., associate professor of public policy at the University of Connecticut, recently spoke at the Bloustein School’s Ruth Ellen Steinman and Edward J. Bloustein Memorial Lecture on the need for reparations for slavery to African Americans.

You may have thought that the time to pay for reparations for slavery was in the immediate aftermath of the civil war – that was done with General William T. Sherman’s Special Field Order 15 in 1865. The order allocated 40 acres and a mule to newly freed people in Georgia. While the order did not pay enslaved people for their lost wages, it did attempt to give them a means to support themselves, feed their families, and live with dignity at a time when society was trying to cope with newly freed people with no obvious means of support.

What happened? President Andrew Johnson rescinded the order and returned the land to its prior owners. So began the era of another exploitive labor practice: the sharecropping system.

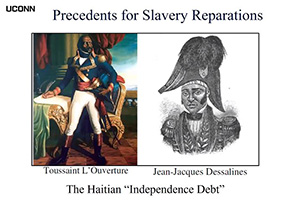

Reparations were typically paid to the enslavers for the loss of their property; enslaved people were not compensated for the loss of their wages or their freedom. Ironically, those who profited were the “victims” of wage theft, not those whose wages were stolen. Haitian and British enslavers were paid for the value of their slaves for a period of over 100 years with final payments not until the late 20th or early 21st century respectively.

In an effort to remedy this injustice Dr. Craemer has explored various options for paying reparations to African-Americans for the enslavement of their ancestors. This would address the wealth gap that exists between whites and African Americans.

Dr. Craemer became interested in reparations as a boy in Germany when the German government began to pay reparations to Holocaust survivors. The government paid pensions to people that were enslaved laborers by the Nazis. A family friend, Mieciu Langer, received a pension from the German government from the 1970’s until his death in 2015 in recognition of his forced labor at several concentration camps prior to and during WWII.

Slave reparations were not unheard of in the U.S. George Washington freed enslaved people that were his personal property when he died and created a fund to assist them. It wasn’t quite reparations, but his actions did recognize a former enslaver’s obligation for the economic support of formerly enslaved people.

When Dr. Craemer came to the United States he was surprised to learn that enslaved people were not compensated for their unpaid wages. In an ironic twist, the U.S. government did try to compensate enslavers for their loss of property; however, the costs of the then-ongoing Civil War made this impossible.

To those who say that no one who is alive today benefitted or was harmed by slavery, Dr. Craemer pointed out institutions such as corporations, the government and plantations all still exit. The decedents of those who were enriched by enslavement benefitted from the wealth their families accumulated. More significantly, generational wealth that built up over time was denied to African Americans due to stolen wages and lives. The generational wealth gap is the difference between the assets that white families own versus the assets at the disposal of African American families. It makes opportunities such as homeownership, higher education, and small business opportunities more difficult for African Americans to pursue because they don’t have access to collateral for down payments, tuition, or investment opportunities.

Many African Americans have had no land or wages with which to make investments or to pass on to subsequent generations. The 2016 household wealth gap was $795,500 with a per capita wealth gap of $338,420. In 2018 the per capita wealth gap between whites and African Americans was $352,250.

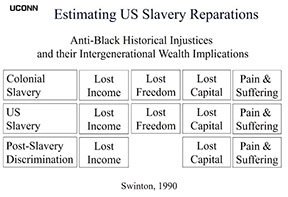

Dr. Craemer explained that there are generally three ways of calculating reparations: land-based, price-based, and wage-based. Land-based reparations could be based on the value of 40 acres and a mule at the time of the liberation of enslaved people and converted into current dollars, with interest compounded annually. Price-based reparations are the value of enslaved labor for the 12 hours a day that a slave worked on a plantation. Wage-based reparations are based on the wages that an enslaved laborer lost for the 24 hours a day that an owner was entitled to the labor of the enslaved worker.

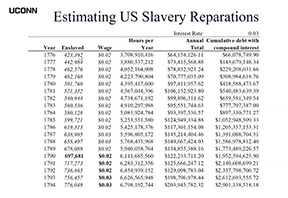

In 2018 dollars, land-based reparations were calculated to total $2.978 trillion. For price- and wage-based reparations, Dr. Craemer used census data to determine the number of enslaved people who lived in the U.S. from 1776 to 1860 and calculated the value of their labor using the wages paid to unskilled workers during that time. He then used a conservative rate of inflation of 3%. This led him to calculate that price-based reparations were $13.2 trillion in 2018 dollars; wage-based reparations came to $18.6 trillion in 2018 dollars.

The final question: how would it be determined who gets reparations? Dr. Craemer suggested that a person who has at least one ancestor who was enslaved and who has identified as African American on official government documents for the last 12 years should receive reparations. This would prevent the 20% of white Americans with some African ancestry from benefiting from reparations.